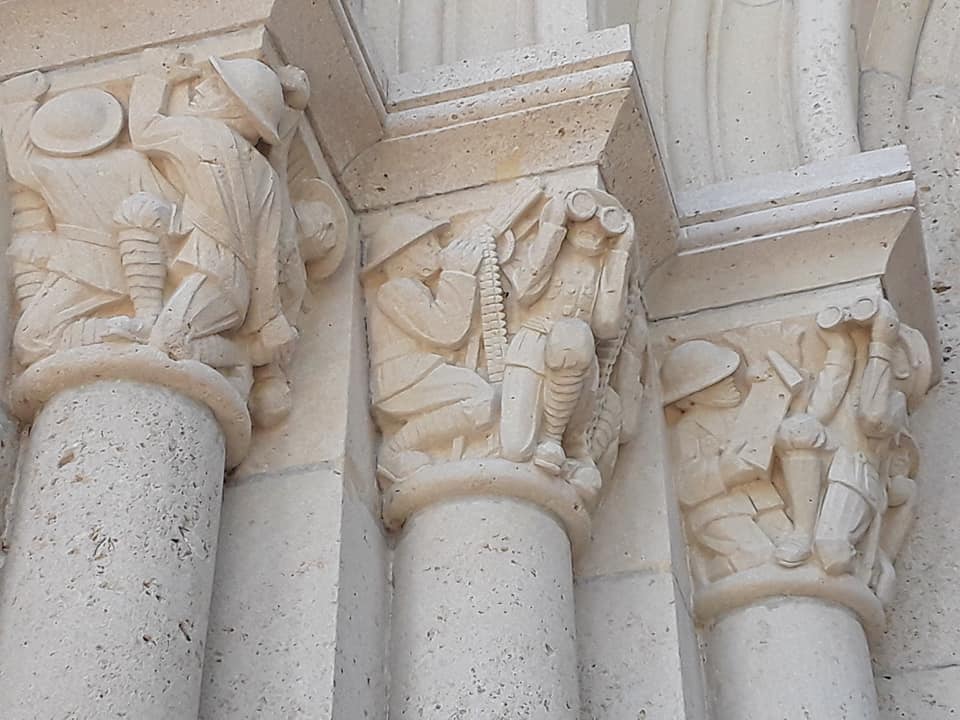

Inside the memorial, a large inscription on an internal surface of the memorial reads:

Here are recorded

names of officers

and men of the

British Armies who fell

on the Somme battlefields

July 1915 February 1918

but to whom

the fortune of war

denied the known

and honoured burial

given to their

comrades in death.

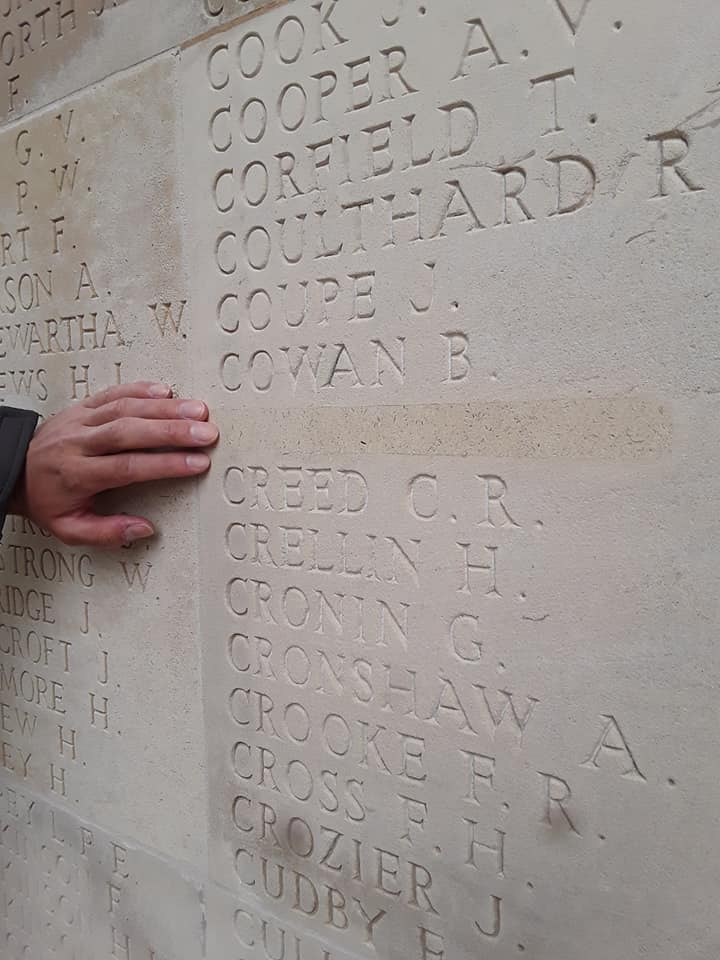

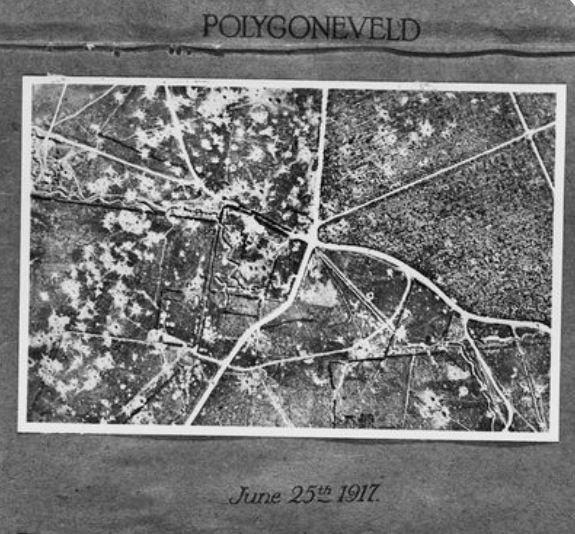

are engraved with over 72,000 names. 90 per cent of these soldiers died in the first Battle of the Somme, between 1 July and 18 November 1916.

Because the monument is reserved for those missing or unidentified soldiers who have no known grave, a soldier’s name is excised from the wall by filling in the inscription with cement when his body is found and identified. The remains are then given a funeral with full military honors at a cemetery close to the location at which they were discovered. This practice has resulted in numerous gaps in the lists of names. 80 names came off the monument 2018.

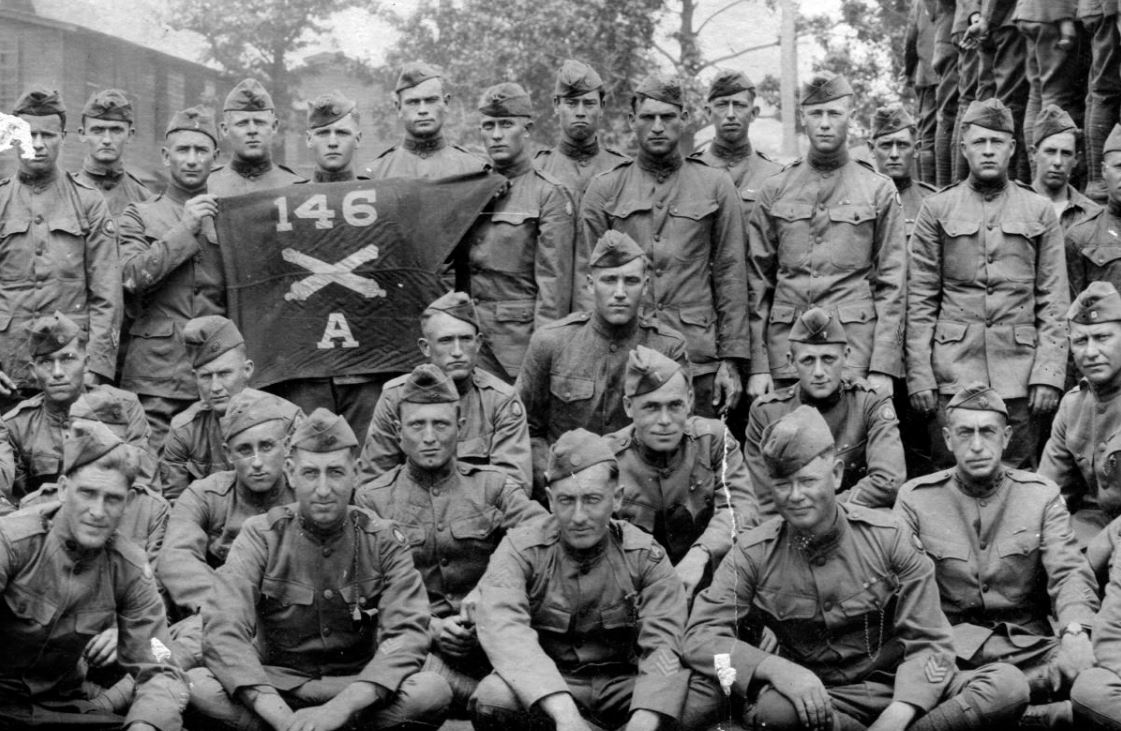

World War I was supposed to be the Great War: the War to End All Wars. Yet here we are, over a hundred years later and wars rage throughout the globe. Clearly, we have not yet learned the lesson such carnage should have taught us.